Kapwa is the understanding that we are never just individuals. We move through life connected—by blood, history, and community—seeing ourselves in one another and carrying each other forward. It’s service without expectation, connection without condition, and the sacred act of showing up.

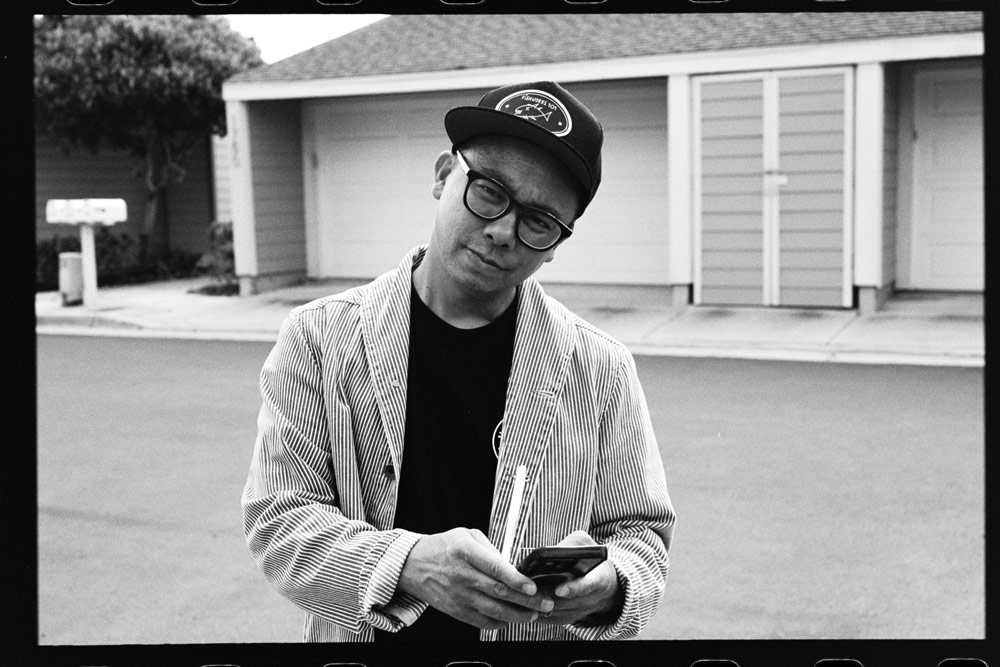

And if Kapwa were a person, it would look a lot like Nino Camilo.

Nino is what happens when talent meets work ethic. A creative force, a cultural connector, and a builder of things that matter. But more than his résumé, what defines him is how he shows up: to help, to uplift, to represent something bigger than himself.

Before poke was a trend or Hawaiian plate lunches went viral, Nino was behind the counter of his family’s island boutique in Pacific Beach, scribbling restaurant recommendations on Post-it notes. That wasn’t just customer service—it was kinship. It was kapwa in motion.

From those humble acts came festivals, blogs, branding campaigns, and community movements. Not because Nino set out to be a founder or a face—but because he kept showing up with sincerity, and trusted that service would open the right doors.

A Childhood Seasoned by Hands and Heart

Nino’s story didn’t begin in a university or a boardroom—it began at home. His first mentor wasn’t a Michelin-starred chef, but his mother, who cooked with instinct and soul. “I didn’t know it at the time,” he says, “but watching her experiment with flavors taught me what good food should taste like. That’s where my palate was built.”

Flavor wasn’t the only thing shaping him. His Auntie Babe and Uncle Rome, co-founders of a Polynesian entertainment group and owners of a Hawaiian specialty shop in San Diego, introduced Nino to the rhythm of work, performance, and purpose. He danced hula on stage. He stocked the store. He listened. He learned.

“I was just a kid,” he says, “but I was surrounded by culture, creativity, and commerce. That gave me my foundation.”

What he absorbed in those years wasn’t just skill—it was identity. And identity, when rooted in service, has a way of carrying you far.

Showing Up, Board in Hand

Like many San Diego locals, Nino grew up surfing. Ocean before obligations. Long breaks when he should’ve been working. Eventually, his uncle pulled him aside and encouraged him to get a job “in the real world.” That led to a position at Starbucks—a high-volume location inside UTC Mall.

There, Nino learned structure. Pace. Teamwork. “You can’t surf your way through a shift at Starbucks,” he laughs. “You learn to show up, clock in, do the work.”

But even while pouring lattes, the dream never left him: to work in the surf industry, not just surf in it.

Where Waves Meet Work Ethic

That dream materialized in an internship at Poor Specimen, the legendary surf film company helmed by Taylor Steele. For any surf kid in the late ’90s or early 2000s, this was sacred ground. Nino entered the room quietly—just another intern, typing emails into spreadsheets on an old iMac. But what he was really doing was absorbing everything.

“I didn’t know it then, but that was my crash course in marketing,” he says. “Before email blasts were a thing, I was building them by hand.”

The rooms he sat in would later become legendary. He watched as Hurley T-shirts made it onto Blink-182 at the VMAs. He helped distribute early Jack Johnson CDs—before the world knew his name.

He wasn’t chasing fame. He was learning rhythm, strategy, intuition. And most of all, how proximity to passion creates possibility.

Then came 2009.

The Recession That Refocused Everything

The action sports industry stalled. Retail slowed. Marketing budgets froze. Nino, like so many, found himself without a job.

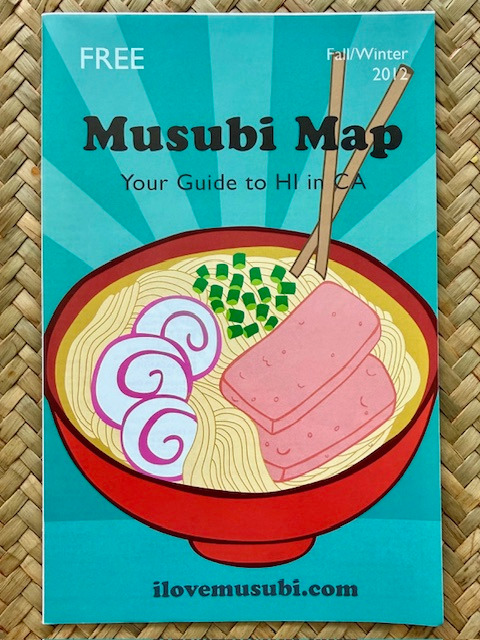

He returned to his family’s store, Motu Hawaii, where the questions hadn’t changed. Tourists and locals alike still asked where to find good Hawaiian food. This time, Nino responded differently. He made a map.

The Musubi Map was a printed directory of island-style restaurants, surf shops, and Japanese markets across Southern California. It was both a resource and a reflection—a way to celebrate the culture that raised him and guide others toward it.

As he crisscrossed Southern California delivering Musubi Maps and documenting island-style food, one thing stood out: nobody really knew where to get good poke. The few places that had it didn’t serve it with the care or flavor he remembered from home. Opening a restaurant wasn’t realistic—he knew what that would take. But creating a space where chefs could come together and celebrate the dish? That felt possible.

So he launched a festival.

I Love Poke: Not Just a Festival.

The first I Love Poke Festival debuted at Bali Hai, a waterfront venue steeped in family history. Nino had no blueprint—only a vision, a community, and the belief that if he honored the culture, people would come.

They did.

Despite pouring rain, the event sold out. Top chefs served their best versions of poke. Aunties offered blessings. Families danced and ate beneath umbrellas, smiling through the storm.

“It wasn’t just about the food,” Nino says. “It was about memory. Ritual. Belonging.”

What started as a local celebration quickly caught attention far beyond San Diego. USA Today named it one of America’s top food festivals. Guests flew in from Canada just to experience it. A poke brand from Australia even launched their new brand at the event.

Still, Nino deflected credit.

“I didn’t start a trend,” he says. “I just served my friends and family. That’s what started everything.”

Then came the pandemic.

The Pivot No One Planned For

Overnight, food festivals disappeared. So did events, income, and the familiar rhythm of doing what Nino did best—bringing people together. But as always, he found a way to help his community.

When the pandemic hit and everything shut down, Nino saw more than just lost income—he saw that people needed something they could count on. Restaurants were scrambling, and families wanted food they could trust—from a face they recognized.

So he reached out to his friends at Fish 101, a beloved North County seafood spot, and offered a simple solution: Let me deliver it myself.

It could’ve been just a side hustle. But for Nino, it was a way to meet a deeper need. He wasn’t just dropping off meals—he was offering a sense of comfort, familiarity, and connection in a time of isolation. He started photographing families on their doorsteps, masked but smiling, proudly holding their Fish 101 dinners. The photos spread across social media—small moments of warmth and community in a season that desperately needed both.

“People couldn’t go out to eat,” he says. “But they could still feel part of something.”

From Delivery Driver to Director

After the pandemic Nino was brought into Fish 101 full-time, eventually stepping into the role of Director of Operations and Merchandise. He helped grow their apparel line into a brand of its own—designing shirts and hats that celebrated surf, fishing, and community, rooted in the lifestyle of coastal San Diego.

“I didn’t create the momentum,” he says. “But I knew how to listen to it, shape it, and honor what the people already loved.”

Whether managing operations, helping with hiring, or solving problems while the owners were away on fishing trips, Nino brought the same humility he carried into every room before: show up, be of use, and serve with sincerity.

Coming Home.

In 2024, a call came from creative agency BLVR. They had been contacted by Valerio’s City Bakery, a cherished Filipino institution founded in 1979, and needed cultural guidance for a rebrand.

Though not part of the agency, Nino was their first call.

What started as a few Zoom calls turned into something deeper. Today, As Operations Manager Nino leads the rebranding and operations of Valerio’s 1979, overseeing locations in Mira Mesa, Cerritos, and beyond. It’s hard work—early mornings, long commutes, new systems—but for Nino, it’s more than a job.

“I’ve been going to Valerio’s since I was a toddler,” he says. “It’s baked into my memory. It’s home.”

“If Fish 101 was about serving community,” he says, “Valerio’s is about serving culture. I couldn’t say no.”

The decision didn’t come easily. Leaving the comfort of a close-knit, beachside team for something uncertain took prayer, thought, and clarity. But one moment made it simple:

“It felt like God was saying—I gave you a chance to serve your community. Now it’s time to serve your culture.”

Rich in the Right Ways

My net worth is my network,” he says. “And I feel like the richest man alive.”

That network wasn’t built through strategy alone, and it definitely wasn’t about self-promotion. It grew out of kapwa—out of doing the work with others in mind, and choosing connection over competition.

Like the crew he jokingly calls the NCAA, the North County Asian Association. A mix of artists, marketers, and business owners who’ve quietly held space for one another in a town where not many people looked like them growing up.

Some say luck is when preparation meets opportunity. But kapwa shows us something else:

When you move through the world with others in mind, you don’t need to chase luck. You’re already part of something bigger.